What is? And what Matters?

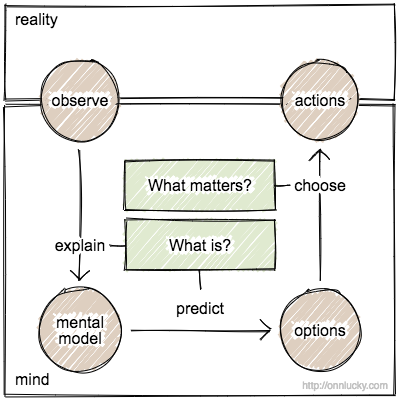

A very useful perspective on life, philosophy and epistemology comes from asking: “what is” and “what matters”. The answers to these two questions are at the center of our choices.

The question “what is” we answer using models that help us to mentally simulate the world. Statistically by knowing tendencies and what is likely. Or from first principles, from knowing rules, the causes and effects, and computing consequences.

The question “what matters” we answer by analyzing our needs, desires, and goals. Guided by examples, stories, and narratives.

When we apply reasoning to the second question, we see that our short term desires often conflict with our longer term goals, and that knowledge is required to reach our goals. Therefor, we do well to keep answers to the second question realistic by using knowledge of the first. However, what is does not dictate what matters.

- “What is?” is sourced from reality and objective.

- “What matters?” is sourced from our personhood and subjective.

Two epistemological mistakes easily made are focusing on explanations instead of predictions (see Proportional Skepticism) or to let “what matters” influence the answers to the “what is” question (see Knowledge, Belief, Attitude).

Consciousness

I wrote a paper on Consciousness From a Learning Perspective (https://psyarxiv.com/387h9)

The big problem in studying consciousness is that we can only measure and observe its objective aspects. Only the conscious person can observe what it feels like to be that person. Yet we would like an answer to the hard problem: what generates consciousness?

One perspective that can give some insight is by looking at learning systems. A system can be said to learn if it is connected to an environment with input, output and feedback. And over time reduces the negative signal in the feedback by responding to input with better output.

Brains are such a system, but they have internalized the feedback by basing it on surprise. To reduce surprise, brains learn to recognize the world, to model it, to predict it; both the external world and the internal mental world. Learning better models and better priorities of their preferences after either negative or rewarding feedback.

To do so, a brain must be processing information and observing itself in a few different ways:

- It has to scan its predictions and judge if there are any dangers or ways to create a benefit;

- It has to match the current situation to predictions and choices made in the past, to see if it needs to learn from what happened;

- To learn and evaluate more abstractly, more causally and over longer time periods, it has to be able to reason and reflect on those reasons, to have thoughts about thoughts.

It is fair to say our brains are self-observers, they observe their own thoughts and observations. Why would that not be conscious? Why would that not be a mind? Enriched with aspects like episodic memory, identity, stories, empathy and love; making it a uniquely human mind.

See also Entropy, Learning & Free Will, What is Understanding?, and From Physics to Meaningful Information

Latest Blog Post: Consciousness and Informational Access

Consciousness is a difficult phenomenon to explain. But key to a possible physicalist explanation is that the brain doesn't just process information, it processes models that process information.