Proportional Skepticism

In every day language, being skeptical means having doubts or reservations. Skepticism in the more philosophical sense it is the stance that real knowledge1 is not possible. Scientific skepticism uses this doubt and the insight that certainty is impossible, to focus on the adequacy of the evidence.

I’ll use the words of Richard Feynman to set the stage.

“We can always prove any definite theory wrong. Notice however, we never proof it right.” — Feynman

“You cannot prove a vague theory wrong.” — Feynman

How do We Come to Knowledge?

I personally like to start with how we come to know things about the world, which is very insightful for what we can expect from our knowledge. To learn about the world we need:

- the ability to observe;

- to recognize patterns in the observations;

- to predict using those patterns;

- to recognize and remember patterns that predict observations well;

- eventually, to figure out the causes behind2 the patterns.

This is how babies begin to learn before they can use reason. That last step is how we come to common sense understandings. This is also how science works, with a strong emphasis on hypothesizing causes and testing their calculated predictions, needed because humans are prone to simplistic intuitions and confirmation bias.

This view on how we form knowledge is itself a pattern, one that predicts that following this pattern is a good way to gain knowledge, a prediction that matches observations. This view on knowledge is self-confirming.

This view also shows why knowledge is so useful. It allows us to make informed guesses about the future, act towards those futures that we want, or try to avoid futures that we don’t want. And we know we are on the right track when our knowledge makes us more effective in the world.

Being Human

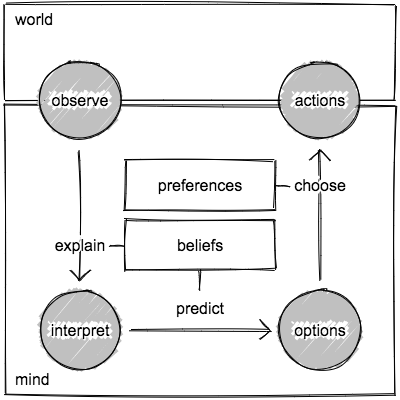

As human beings, we look for more than just knowledge, we also look for meaning. We want to know what our options are and we want to make choices in line with our values and our preferences. The full picture looks like this:

Our knowledge is a collection of beliefs, these beliefs should explain what is going on and predict the options that are available. Our preferences should inform which option to choose. When we are not as effective as we want to be, we should try to update some of our beliefs or our preferences or both. But this is the hard part:

- How do you recognize your own ineffectiveness?

- How do you recognize an incorrect belief?

- How do you recognize what you really want?

In essence, all we observe3 is light coming in through our eyes and sounds vibrating in our ears. We have to interpret these observations using layers of beliefs before we can recognize the more complicated systems4. What if this process went wrong somewhere and you find yourself with a set of mostly consistent beliefs, but unable to see that some are incorrect.

Role of Skepticism

This is where skepticism can play a role. Instead of holding on to beliefs dogmatically, you should use them where they make you effective. And instead of going all in, or all out, you should trust a belief proportionally to the evidence you have for it.

The diagram above shows two important things about beliefs:

- Beliefs should predict as well as explain;

- Preferences should only be involved in choices, and have no place in beliefs, explanations or predications.

Otherwise your beliefs might feel justified, while they are not, because:

- When a belief is vague, it can explain anything;

- When preferences are used to select the evidence, any belief can be confirmed.

Or using the words of Prof. Feynman again:

“If the process of computing the consequence is indefinite, then with a little skill, any experimental result can be made to look like an expected consequence.” — Feynman

-

This is easily misunderstood as the claim that nothing can be know about the world. That such a skeptic would not even be able to eat, not knowing what food is. But knowledge here is defined in philosophical terms as justified true beliefs. And from an epistemological perspective that definition has all kinds of problems, or so the skeptic would argue. A skeptic would eat, knowing he could be wrong about what he is about to put in his mouth. The food might have spoiled and make him sick, might have been poisoned and kill him, or might be a skillfully crafted replica with zero taste or calories. ↩

-

One example is math, we notice the pattern of one thing, then another thing, always leads to two things. A different type of example is fire, for a long time humans knew how to make fire and how to keep it under control. But only with modern science we could figure out the underlying causes, namely sustained exothermic chemical reactions. ↩

-

We also observe our own mind. We can observe our emotional states. And we can observe our beliefs, our preferences and our thought process. ↩

-

Think about the value of a hundred dollar bill. It’s just atoms arranged in certain ways. But we recognize the printing on it as numbers. We recognize how long we have to work to earn it, how easily it is spend. We have some idea on how the economy works, the government that prints it, etc., layers upon layers of systems and interpretations. ↩