Knowledge, Belief, Attitude

In social psychology knowledge, attitude, belief is an often used model for what goes on in our minds. I find it very useful when talking about beliefs:

In social psychology knowledge, attitude, belief is an often used model for what goes on in our minds. I find it very useful when talking about beliefs:

- knowledge: facts, causal relations, or mental models within a certain domain;

- belief: how correct is a piece of knowledge given its domain;

- attitude: does it matter (to me or others); is it morally good or bad1.

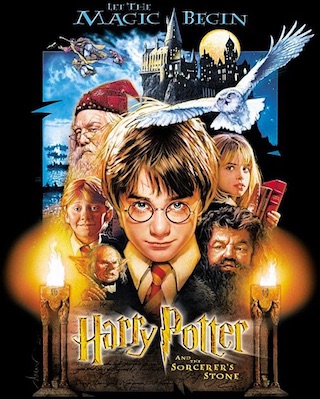

For example: “Harry Potter is a wizard” is a piece of knowledge. I believe it to be correct given that it relates to this fantasy world invented by J.K. Rowling. From an attitude perspective, some people might think the stories invite magic and occult forces and are therefor evil; others might think it fosters supernatural intuitions about the real world and thus hurt education; though for most it is just harmless entertainment.

Attitudes Inform Beliefs

What happens a lot is that our attitudes inform our beliefs, even when the belief is about reality. This is a mistake. For example, we might think that a hurricane approaching our city is bad, but such an attitude will never change reality, so be prepared or evacuate. Yet aligning our attitudes with our peers is normal, it enables shared intentions and avoids conflict. For example, if most people believe that graveyards are sacred places, violating that sacredness reduces ones standing in the community and risks punishment. Honest mistakes about sacred things might be forgiven. Honest mistakes about reality, however, do nothing for the potentially devastating effects.

Beliefs about reality informed by attitudes are easy to spot using the following markers2:

- People holding them will be selectively skeptic, that is, they will seem to be weighting the evidence for two competing models of the world differently. Adding on more and more excuses or ad-hoc explanations to maintain the belief.

- Because such beliefs are linked to values and morality, such people are quick to accuse those with different ideas as immoral. But without being able to point out any evidence of bad behavior or even bad intentions. At best they argue about some indirect consequences they think will come about — often using the very ideas in dispute.

- Using the emotive conjugation a lot without objective justification. For example, after a debate, describing one side as: stubborn (negative); didn’t change his/her mind (neutral); unwavering in the truth (positive).

Warning

But a big warning is required here. It is very easy to see this behavior in others even when it is not there, while not recognizing this behavior in ourselves. The only antidote is understanding the position of the other person from a knowledge perspective. That is, being able to reason about it, while not believing it and not accepting the values or morality behind it. And to try and look at our own beliefs as objectively as possible.

Have “strong opinions, weakly held”. And know that in the context of knowledge, changing ones mind based on evidence is a virtue. (Also see previous.)

Right, but for the Wrong Reasons

What can happen (a lot) is that people are on the side that has the most reason and evidence behind it. But the issue has become very personal, political and moralizing. They go into arguments using all the markers discussed above. Becoming less and less effective in convincing others, while blaming it more and more on how stupid those with different beliefs must be.

-

In a weird meta way, what we believe and what matters to us, is also knowledge. Knowledge in the domain of beliefs, and knowledge in the domain of what matters. ↩

-

Using this idea, we can score discussions purely based on markers, requiring minimal knowledge of the subject matter:

- articulate a tradeoff (+2);

- fairly articulate opposing view (+2);

- reasons based on content (+1);

- using a fallacy (-1);

- using a straw man (-2);

- ad hominem attacks (-3);

- guessing moral attitude of opponent (-10).